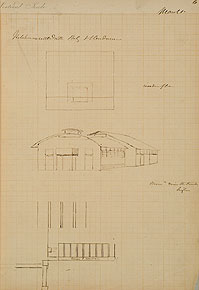

Sketch and plan of Renkioi hospital

(University of Bristol)

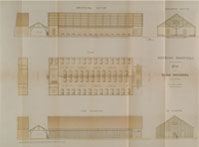

Original proposal for Great Exhibition

Hall (University of Bristol)

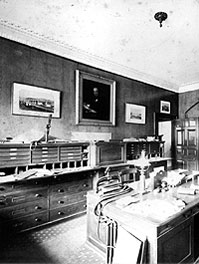

Brunel’s office at his home in Duke

Street, London (Elton Engineering)

Opening of Royal Albert Bridge

(Elton Collection: Ironbridge Gorge

Museum Trust)

The

1840s and 1850s

Brunel worked long hours and was frequently away on business, but still

found time to entertain his children with nursery games and conjuring.

In 1843, he accidentally swallowed a half-sovereign he was using in one

of his tricks. It lodged in his windpipe and threatened to choke him to

death. A tracheotomy was performed by a leading surgeon with two-foot

long forceps but was unsuccessful. Showing his ingenuity and sang-froid,

Brunel devised a board, pivoted between two uprights, to which he was

strapped and rapidly turned head over heels. The centrifugal force dislodged

the coin, which dropped from his mouth.

In 1850, Brunel became involved in preparations for the Great

Exhibition of Science and Industry of All Nations to be held in Hyde Park

the following year. He contributed to early designs for an exhibition

space and in the arrangements for the opening parade. When Paxton’s

Crystal Palace was relocated to Sydenham, Brunel designed two water towers

for the site. (Read more about the Great Exhibition on the Arts

and Culture page).

In 1853, work began on Brunel’s biggest maritime project: the ss

Great Eastern. (Read more about the ship on the Major

Projects page). At the same time, Brunel was also supervising the

construction of another of his engineering triumphs, the Royal Albert

Bridge which carried the Cornwall Railway line over the Tamar at Saltash.

This was completed in 1859.

In February 1855, Brunel was invited by the Permanent Under

Secretary at the War Office, Sir Benjamin Hawes (husband of his sister

Sophia), to design a pre-fabricated hospital for use in the Crimea that

could be built in Britain and shipped out for speedy erection at a chosen

site. The design took six days to complete and the parts reached Renkioi

in the Dardanelles in May that year. By July it was ready to admit its

first 300 patients and by December had reached its capacity of 1,000 beds.

On his doctor’s advice, Brunel travelled to the Alps, Vichy and

Egypt during 1858. He was suffering from Bright’s disease and had

endured years of physical and mental strain. On Christmas Day he dined

in Cairo with Robert Stephenson, his old friend and colleague, who had

similarly ruined his health through overwork. Despite deriving some initial

benefit from the change of scene, when Brunel returned to Britain the

stress associated with the ss Great Eastern project intensified and he

collapsed with a stroke on 5 September 1859. He died at his Westminster

home ten days later.

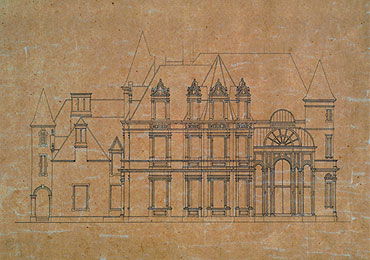

Architect’s drawing of Brunel’s proposed home

on his Watcombe estate

(University of Bristol)

Brunel was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery on 20 September 1859. The route

to the cemetery was lined with thousands of railwaymen and members of

the public. His friend and colleague Daniel Gooch wrote in his diary:

I lost my oldest and best friend... By his death the greatest of England’s

engineers was lost, the man with the greatest originality of thought and

power of execution, bold in his plans but right. The commercial world

thought him extravagant; but although he was so, great things are not

done by those who sit down and count the cost of every thought and act.