Portrait

of Marc Brunel (ICE)

Page

from report by Brunel’s assistant

Richard Beamish (ICE)

Brunel’s

journal entry 29 June 1827

(University of Bristol)

Company

medallion

(University of Bristol)

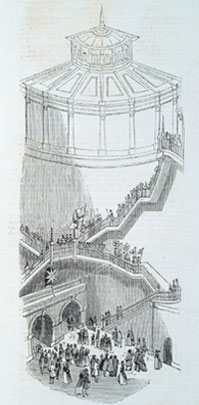

Opening

ceremony

(University

of Bristol)

Marc

Brunel bidding farewell to crowd

(University of Bristol)

Thames

Tunnel aquatint

(Elton Collection: Ironbridge Gorge

Museum Trust)

The

Thames Tunnel

By the early nineteenth century, congestion in London, particularly around

the busy dockyards in the east, was acute, exacerbated by the presence

of the foul smelling River Thames, which cut the city in two. The construction

of more bridges might have helped relieve the problem but they would need

to be built high enough to allow the passage of ships.

Looking for an alternative, the Thames Archway Company was formed in 1805

with the intention of constructing a tunnel to run beneath the river.

Richard Trevithick, a Cornish miner and engineer, was appointed to supervise

the initial stages, digging a pilot tunnel or driftaway. However, the

traditional method of shoring up the tunnel sides and roof with timber

proved unsuccessful in these difficult conditions and after a series of

floods, the pilot was abandoned just 200ft/61m short of its target. The

Thames Archway Company was dissolved in 1809.

In 1818, Marc Brunel patented a tunnelling shield made from iron, inspired

by the head of the ship-worm which could bore through ship’s timbers.

Miners would work in a series of compartments inside the shield, excavating

sections of earth held back by heavy wooden boards, which were removed

and replaced one at a time to allow access to the face. Meanwhile, bricklayers,

working close behind the shield, would be constructing the tunnel lining.

When all the earth within reach of the boards had been dug out, the shield

could be moved forward to begin the process again.

Convinced that the shield made the scheme to build a tunnel beneath the

Thames a feasible proposition, the Thames Tunnel Company was formed in

1824 with Marc Brunel appointed as chief engineer. Work began near the

church of St Mary’s Rotherhithe in March 1825. A huge cylinder of

brickwork, 50ft/15.24m in diameter and 42ft/12.8m high, was built upon

an iron ring. As the brickwork was completed, workmen dug away the ground

inside and beneath the ring. The weight of the bricks caused the cylinder

to slowly sink until its top reached ground level. The tunnelling shield

was then lowered into the shaft to begin its laborious progress beneath

the river.

It had been assumed that the miners would encounter firm clay throughout

their passage but the shield soon struck loose gravel and sand mixed with

rotting sewage, making the work even more dangerous and difficult than

expected. The foul air in the tunnel caused fevers and blindness. One

victim was William Armstrong, the engineer-in-charge, who suffered serious

illness. He resigned and Marc’s son Isambard was promoted to replace

him. Eager to prove himself, Brunel often spent days at a time underground,

taking only short naps between shifts, lying on a bricklayer’s stage

beside the shield. Fearful for his health, Marc assigned him three assistants

in a vain attempt to reduce his punishing workload: one died of fever,

another lost his vision in his left eye.

Although the bricklayers worked fast, there was always a risk that the

water would break through the unsupported gap beneath the riverbed that

was exposed each time the shield was moved forward. On 18 May 1827, the

river burst in and a great wave rushed through the tunnel. Fortunately,

the men had time to reach the shaft and were able to climb the stairs

to the surface before the tunnel flooded. Displaying his typical bravery,

Brunel rescued an old man who was struggling in the rising water by sliding

down an iron tie rod and securing a rope around the man’s waist.

Within 24 hours, Brunel was inside a diving bell, borrowed from the West

India Dock Company, inspecting the hole in the tunnel roof that had caused

the flood, one foot resting on the completed brickwork, the other on the

shield. His companion lost his hold upon the diving bell and had to grab

Brunel’s extended foot to avoid disappearing down the hole to a

certain death. Brunel dragged him back up and returned to the surface

before descending once more to continue his inspection. Later, when the

hole was filled with a combination of iron rods and bags of clay, Brunel

was the first to reach the shield, initially by boat on the floodwaters

and then by crawling over the bank of earth the river had washed in. In

his diary he wrote:

What a dream it now appears to me! Going down in the diving bell,

finding and examining the hole!... The novelty of the thing, the excitement

of the occasional risk attending our submarine

excursions, the crowd of boats to witness our works all amused –

the anxious watching of the shaft – seeing it full of water, rising

and falling with the tide with the most provoking regularity...

Work resumed in November, an occasion marked by a banquet held within

the tunnel, but disaster struck again in January 1828 when water burst

in with even greater ferocity. Brunel was standing in the shield at the

time and was swept away. He was trapped beneath a fallen timber, which

damaged his knee and caused internal injuries. Managing to free himself,

he waited and called out for the men he thought had been lost beneath

the collapsed staging. He later wrote:

While standing there the effect was – grand – the roar

of the rushing water in a confined passage and by its velocity rushing

past the opening was grand, very grand. I cannot compare it to anything,

cannon can be nothing to it. At last it came bursting through the opening.

I was then obliged to be off – but up to that moment, as far as

my sensations were concerned, and distinct from the idea of the loss of

the six poor fellows whose death I could not then foresee, kept there.

The sight and the whole affair was well worth the risk and I would willingly

pay my share, £50 about, of the expenses of such a ‘spectacle’.

With his injuries, Brunel’s association with the tunnel ended. Although

Marc was again able to fill the breach, work came to a halt as the finances

were exhausted and business confidence in the project was lost.

Marc persevered and work finally resumed in 1835. The Thames Tunnel was

opened to the foot traffic on 25 March 1843. It was the first tunnel to

be built under a navigable river and hailed as the eighth wonder of the

world. In 1869, it was converted to carry the East London Railway. Today

around 14 million passengers travel through it each year.