Medieval court, Great Exhibition

(Elton Collection: Ironbridge Gorge

Museum Trust)

Art

and Industry

In 1851, six million people visited The Great Exhibition of the Works

of Science and Industry of all Nations held in the Crystal Palace, a magnificent

purpose-built construction of glass and iron designed by Joseph Paxton.

Brunel was on the organising committee for the exhibition. All 245 entries

in a competition to design an exhibition space were rejected and Brunel

joined the building sub-committee, which came up with an extraordinarily

ugly brick-built structure with a squat, sheet-iron dome. The public outcry

that broke out when pictures of the design were released led to calls

to move the exhibition site further out of London, a proposal only narrowly

beaten in the Commons. Promoter Henry Cole encouraged Paxton, who had

not entered the original competition, to submit his own design. A ‘sneak

preview’ was shown in the Illustrated London News of 6 July and

a week later was formally approved by the committee.

The exhibition was said to have been originally proposed by Prince Albert

and aimed to promote and celebrate the achievements of the Industrial

Revolution. More than 100,000 exhibits were on show, organised into four

categories: raw materials, machinery, manufactured goods, and fine arts.

In addition to the international collection on display there were organised

events, including the popular organ concerts, and the fountains in and

around the Crystal Palace created a spectacular water feature, with the

jets reaching heights of 250 feet. Special excursion trains were organised

to bring in visitors from outside the city. The exhibition and the extraordinary

Palace constructed to house it symbolised for many the triumph of the

industrial age, a marker of the rise of technological innovation and of

globalisation. Furthermore, the exhibition profits supported the foundation

of new public museums, such as the Science Museum, Natural History Museum

and V&A in Kensington.

Prince Albert had wanted to demonstrate through the exhibition that industrialisation

could produce beautiful as well as useful goods, and the exhibits included

a considerable variety of arts and crafts. For many, the most beautiful

work of art on view was the Crystal Palace itself. However, some remained

unconvinced that the artistic could co-exist with the industrialised.

Key among these were the members of the Arts and Crafts movement and in

particular its founder Williams Morris. Morris, a socialist and member

of the pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, rejected mass production in the same

way he rejected social injustice, feeling the two were inextricably linked.

In 1861, he founded a design company that created a range of products

(wallpaper, furniture, tiles, stain glass, silver work, fabrics) using

traditional techniques and handcrafting. Ironically, the designs proved

so popular they were copied by manufacturers and mass-produced.

With the closing of the Great Exhibition, the Crystal Palace was dismantled

and re-erected at Sydenham Hill. It was reopened on 10 June 1854 by Queen

Victoria and became what might be termed a Victorian theme-park, popularly

known as the Palace of the People. Brunel designed two water towers, each

carrying 3,000 tons of water, for the new site.

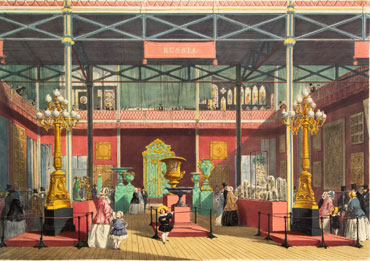

Russian displays, Great Exhibition: Dickinson Brothers lithograph

(Elton

Collection: Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust)