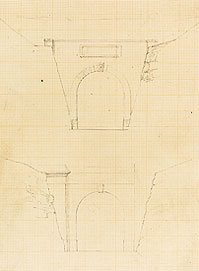

Brunel’s

sketch for Box Tunnel

(University of Bristol)

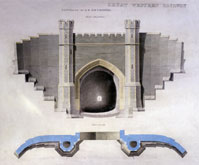

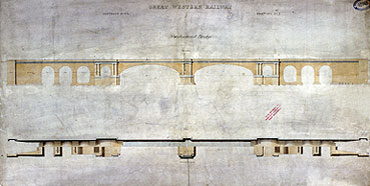

Contractor’s

drawing of Twerton Tunel

drawn to Brunel’s specifications

(Adrian Vaughan Collection)

Exterior

of Brunel’s Temple Meads

station at Bristol (National Trust)

The

last GWR broad gauge locomotive

running from Paddington to Penzance,

1892 (Private collection)

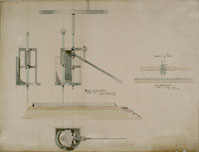

Brunel

sketch of pumping station

for atmospheric railway

(University of Bristol)

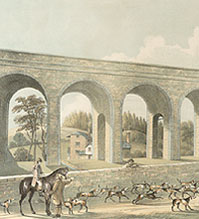

Slade

viaduct on the South Devon

Railway (National Trust)

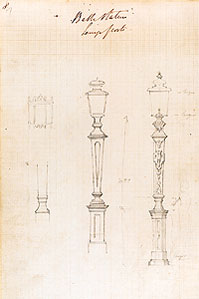

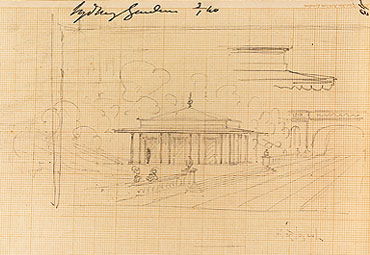

Brunel

sketches of lamp posts at Bath

and Bristol (University of Bristol)

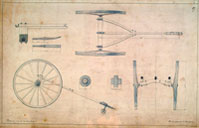

‘ Contractors’

tools designed to Brunel’s

specifications (University of Bristol)

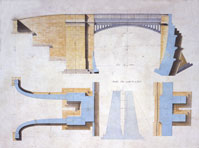

Contractors'

drawing of iron bridge

at Sydney Gardens, Bath

(Adrian Vaughan Collection)

Wooden

viaduct, as used on the

Cornwall and West Cornwall Railways

(Elton Collection: Ironbridge Gorge

Museum

Trust)

During

Brunel’s years in office he became personally involved in every

aspect of the enterprise and insisted on the highest standards of workmanship

throughout. He negotiated with the clients, designed the track layout

and rolling stock, devised radical solutions to civil engineering problems,

secured finance, and recruited, motivated and managed staff. To complete

the survey of the line, Brunel designed a black travelling carriage called

a britzka to carry his drawing board, outline plans, engineering instruments,

50 of his favourite cigars and a pull-out bed.

A private bill was submitted to Parliament in 1834 to allow the

compulsory purchase of land along the chosen route. This was rejected

but a new bill was submitted the following year, with Brunel presenting

GWR’s case. Thanks to his eloquence and enthusiasm, the bill received

Royal Assent on 31 August 1835. Over the next six years, Brunel’s

technical ingenuity was tested by the terrain he crossed and among his

lasting achievements are the bridge at Maidenhead, the viaducts at Hanwell

and Chippenham, and the two-mile-long Box Tunnel. Between the Bath and

Bristol section alone, there are three viaducts, four major bridges and

seven tunnels. Writing of Brunel’s achievement, Kenneth Clark wrote:

Every bridge and every tunnel was a drama, demanding incredible feats

of imagination, energy and persuasion, and producing works of great splendour.

Contractor’s drawing based on Brunel’s

specification for Maidenhead bridge (Adrian Vaughan Collection)

On 30 June 1841 the GWR directors left London on their inaugural

journey down the length of Brunel’s track and arrived in Bristol

only four hours later. From the outset Brunel declared that his route

would be the best but not necessarily the cheapest. The work had cost

£6.5m: more than double the original estimate.

GWR running through Bath to Bristol (National Tust)

Brunel’s sketch for Sydney Gardens, Bath (University

of Bristol)

Brunel was involved in all aspects of the design of the station at Bristol

Temple Meads, one of the oldest surviving railway terminuses in the world,

although it has not been used as such since 1965. At one time the building

housed the Bristol Exploratory hands-on science centre. It currently provides

a home for the British Empire and Commonwealth Museum. Temple Meads is

thought to be the first true ‘terminus’ type of railway station

in which trains and people inhabited the same space beneath a single over-sailing

roof. Some contemporary critics considered the turrets, façades

and decoration were inappropriate and anachronistic, but it is today admired

for the way style, space and structure come together naturally and

coherently. Geoffrey Channon in his account of the promotion of the GWR

has written that opponents to the GWR Bill persistently argued about the

location for the Bristol station:

As generations of tired travellers have observed, the terminus was

chosen on a site which was near to the centre of the ancient city but

not in it... A small sub-committee of three directors examined the matter.

Brunel took them to the top of St Mary Redcliffe Church to survey the

various options. From there it was apparent that Temple Meads was the

only site that had plenty of space to develop depots and other facilities.

Brunel had insisted on using his broad gauge (7ft/2.14m) system instead

of the standard gauge (4ft 8.5/1.43 m) endorsed by Robert and George Stephenson.

This led to difficulties when the two gauges met as passengers had to

transfer trains. With carriages and locomotives designed by Daniel Gooch

to Brunel’s specifications, the broad gauge system was more comfortable

and allowed for faster travel than the narrower gauge. However, in 1846

the government decided in favour of the standard and all new lines were

built to that gauge (the GWR would complete its conversion to standard

in 1892). The government’s decision made economic sense as by that

time 2,000 miles of standard gauge track had been lain compared with only

300 of broad. Unlike the Stephensons, Brunel did not appear to have a

vision of a national rail network using the same gauge: he saw the GWR

as a self-contained route. Writing in his diary, Gooch wrote of the battle

of the gauges:

Were the whole question now open to be decided, the broad gauge is

safer, cheaper, more comfortable, and attains a much higher speed than

the narrow, and would be best for the national gauge. But as the proportion

of broad to narrow is small, there is no doubt the country must submit

to a gradual displacement of the broad, and the day will come when it

will cease. The fight has been of great benefit to the public; it has

pricked on all parties to exertion; the competition of the gauges has

introduction high speeds and great improvements to engines, and was of

great practical use to all those who were actively mixed in the contest,

as they were forced to think and experiment.

Dawn

near Reading, showing a west-bound GWR train c. 1870, artist unkown (Elton

Collection: Ironbridge Gorge Museum

Trust)

Over the next 20 years, the GWR and its associated lines, including the

Bristol and Exeter, South Devon and Cornwall Railways, rapidly spread

throughout the South West, South Wales and Midlands. Part of the South

Devon route was originally designed to be worked by an atmospheric system.

Brunel had thought the system would allow him to adopt stiffer gradients

through the difficult coastal terrain: the developments in the capabilities

of steam locomotives soon made this advantage obsolete. After a series

of trial runs, it was announced at a meeting of shareholders at the Royal

Hotel in Plymouth on 29 August 1848 that the atmospheric system was to

be abandoned.

Through his work on the railway, Brunel contributed to a process that

would come to physically unify the country, conquer distances, widen access

to public transport, and lead to the general adoption of Greenwich Meantime.

By the end of his career it is estimated that Brunel was responsible for

laying nearly 1,200 miles of track including stretches in Italy, Ireland

and Bengal.

As with any project he undertook, Brunel set his personal stamp on the

Great Western Railway. His reluctance to delegate meant every aspect of

the line reflected him as an engineer. Although other railway engineers

may have produced more miles of track and more economically, no other

rail system was so influenced by a single creative genius. Brunel wanted

to build not just the rail route, but the gauge, the engines, the civil

engineering structures and everything else connected to it.

Brunel’s Great Western Railway enhanced the transport and

communication facilities offered by Bristol, and strengthened it as a

regional centre and as a gateway to the South West. Much of the route

Brunel mapped out and the bridges, viaducts, cuttings and tunnels he constructed

continue to be used today. There is a campaign to attain World Heritage

Site status for this route and the ‘pearls’ strung along it

between London and Bristol, including Paddington station, Wharncliffe

Viaduct, the Maidenhead Bridge, Swindon Railway Village, Wootton Bassett

Incline, Box Tunnel, Sydney Gardens and Temple Meads Passenger Shed.

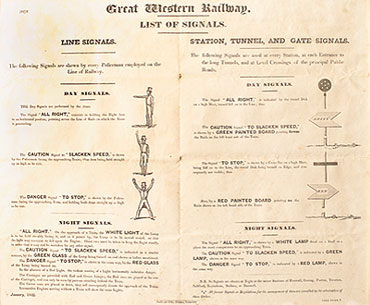

Great Western Railway information leaflet for signalling

systems

(National

Trust)