Selection

of artist’s impressions of

entries to the competition by Capper,

Motley and Armstrong

(University of Bristol)

Artist’s

impression of Thomas Telford’s

design (ICE)

Portrait

of Telford (University of Bristol)

Artist’s

impression of Brunel’s gateway

to bridge (University of Bristol)

Detail

from The Ceremony of Laying the

Foundation Stone of the Suspension

Bridge by Samuel Colman (Bristol

Museums and Art Gallery)

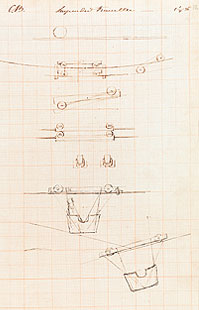

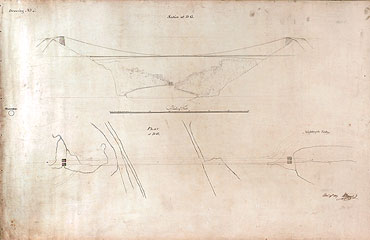

Brunel’s

sketch of cradle for working

on the bridge (University of Bristol)

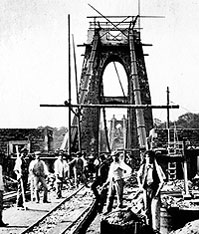

Bridge

under construction

(Clifton Suspension Bridge Trust)

Hotwell

House and piers of suspension

bridge (University of Bristol)

Front page coverage of opening of

bridge

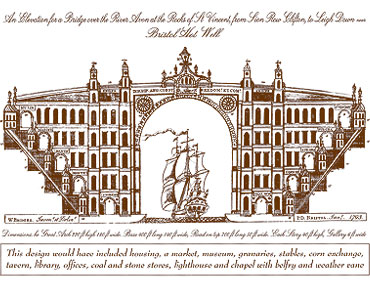

Design for a bridge across the Avon by William Bridges 1793

(University of Bristol)

In

1754, William Vick, a wealthy Bristol wine merchant, had left

£1,000 in his will with instructions that the money should be invested

until it reached the sum of £10,000, an amount he felt would pay

for the construction of a stone bridge across the gorge. The bridge would

be free to travellers and would link the hamlet of Clifton and the private

estates of Leigh Woods. As the proposed bridge would seem to serve little

economic purpose, it is uncertain what Vick’s motive was in leaving

these instructions.

Brunel’s winning entry

By 1829, Vick’s legacy had reached £8,000 and a committee

was set up to decide how to fulfil his dream. It was soon realised that

a stone bridge would cost in the region of £90,000. An iron suspension

bridge would be cheaper but would still require tolls to cover its cost

and maintenance. An Act of Parliament was passed allowing these changes

to Vick’s bequest and on 1 October a competition to design a bridge

was announced with a prize of 100 guineas for the winner.

Brunel entered the competition but the result was a shambles: the judge,

the distinguished engineer Thomas Telford, dismissed all the entries and

was invited to submit his own proposal by the committee. Telford’s

design, a three span bridge supported by Gothic towers (he thought the

span too great for a suspension bridge), was derided by the public. A

second competition was announced in 1830 and once again Brunel submitted

four designs. One of these was originally given second place but Brunel

convinced the panel to award him the first prize: this was formally confirmed

on 16 March 1831. He wrote to his brother-in-law:

I have to say that of all the wonderful feats I have performed since

I have been in this part of the world, I think yesterday I performed the

most wonderful. I produced unanimity amongst fifteen men who were quarrelling

about the most ticklish subject – taste.

The Egyptian thing I brought down was quite extravagantly admired by all

and unanimously adopted; and I am directed to make such drawings, lithographs,

etc as I, in my supreme judgement, may deem fit; indeed, they were not

only very liberal with their money, but inclined to save themselves much

trouble by placing very complete reliance on me.

His design shows that Brunel perceived the bridge in terms of the grand

experience of crossing the gorge, of having a landmark presence and of

being a gateway to the city. Author Bryan Little has written of the project:

...with his piercing, inventive brain, [Brunel] was as much artist

as engineer. His earliest Bristol activity led to the creation of a great

engineering feat which he also saw as a conscious work of art… His

essentially artistic conception led on to his more utilitarian, and not

less famous work, on the harbour, on steamships, and on the railways.

On 21 June 1831, at the ceremony to mark the laying of the

foundation stone on the Clifton side of the gorge, Sir Abraham Elton,

referring to Brunel, said:

The time will come when, as that gentleman walks along the streets

or as he passes from city to city, the cry would be raised, "There

goes the man who reared that stupendous work, the ornament of Bristol

and the wonder of the age".

1851 watercolour showing Clifton-side tower of bridge and

the observatory (Private collection)

In late October that year, Bristol suffered considerable damage and disruption

during rioting centred upon Queen Square. Brunel, who was in the city

to supervise work on the bridge, served as a special constable during

the riot. Business confidence in the city fell and work on the bridge

was halted. It did not resume until 1836.

Brunel referred to the Clifton Suspension Bridge as his ‘darling’

but financial difficulties and contractual disagreements led to long delays

in its construction and the bridge was not completed until 1864, five

years after his death and as a memorial to him.

Brunel's Hungerford Suspension Bridge: demolished to make

way for a new bridge at Charing Cross, its chains were used at Clifton

(Elton Collection: Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust)

The bridge spans 214 metres between its two 26 metre high towers and stands

76 metres above the high water mark in the gorge through which the river

Avon flows. Modern computer analysis has revealed that in his design of

the crucial joints between the 4,200 links that make up the bridge’s

chain, Brunel had made an almost perfect calculation of the minimal weight

required to maintain maximum strength (the chains were taken from his

bridge at Hungerford which had been demolished). In 2002, it was discovered

that the bridge’s abutments contain a honeycomb of chambers and

tunnels, some of which are 11 metres high. It is thought that these spectacular

vaults reduced the cost of construction without reducing strength.

Although built for pedestrian and horse drawn traffic, the bridge was

so ingeniously constructed that it is now capable of carrying around 4

million cars a year, and has become a major route to the motorway network.

It is also a structure of great beauty and in 2006 this will be enhanced

with a new lighting scheme, to be revealed on the anniversary of Brunel’s

birth.

The Clifton Suspension Bridge is one of Bristol’s cultural icons

and provides perhaps the most easily recognised visual image of the city,

being used as a logo on publicity material produced by Destination Bristol

and other local bodies. It is symbolic of the city’s history of

building bridges between different communities, places and sectors and

its chequered history epitomises the clash between innovation and conservatism

that has characterised much of Bristol’s development.

In 1998, the Clifton Suspension Bridge Trust opened a visitor centre,

telling the story of the bridge through exhibitions, photographs, art

work, memorabilia, models and interactive displays.

Visit the official website of the Clifton

Suspension Bridge for further details of the bridge’s history

and construction.

Photograph of the bridge today (Destination Bristol)