Early railway track at Prior Park, Bath

(Elton Collection: Ironbridge Gorge

Museum Trust)

Steam power not only transformed the production process but also the means of distribution. Although steam had its limitations, it was generally more consistent and reliable than previous sources of energy. As a result, when it was harnessed to a transport system, there could be greater confidence in the delivery of supplies and products.

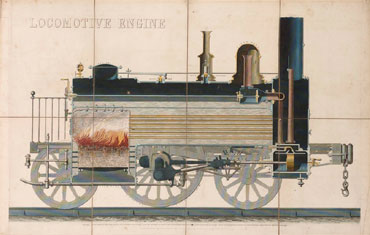

Victorian educational aid showing steam locomotive (Private collection)

Although there were attempts to manufacture steam coaches that ran on roads, the most effective means of steam locomotion on land was upon tracks. Before the age of steam, tracks were already being laid in collieries where they were used by horse drawn coal wagons, the track easing the passage of the wheels. The first complete track of cast iron rails, as opposed to wooden ones, was built in 1767 at Coalbrookdale in Derby. The Surrey Iron Railway, which opened in 1805 to transport merchandise from Wandsworth to Croydon, is considered to be the first public railway. A single horse was able to pull a heavy load with ease along this track at an average speed of 6mph.

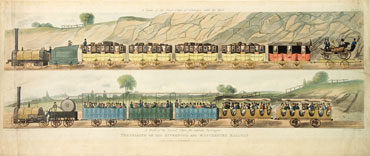

Steam locomotion on circular rail tracks occasionally provided novelty rides at the turn of the century, but it was George Stephenson (1781-1848) who was instrumental in developing the process for wider commercial use. He built his first steam locomotive in 1813. Like Watt, Stephenson improved on earlier engineering designs and his locomotives were more reliable than anything that had come before, capable of pulling 30 ton loads of coal. As a result of his success he was invited to build an eight-mile track from Hetton to Sunderland and later worked on the Stockton-Darlington line, which was constructed between 1822 and 1825. Stephenson’s gauge of 4ft 8.5 / 1.43m was to become the national standard, although Brunel’s broad gauge is now thought to have provided faster and more comfortable journeys. It was on the Stockton-Darlington line that the first railway passenger coach was introduced. Stephenson’s famous Rocket won trials held in 1829 to select the locomotive design to be used on the new Liverpool-Manchester railway. Stephenson’s son Robert (1803-1859) worked on a number of his father’s projects and was considered part of the Great Triumvirate of mid-century British railway engineering along with Brunel and Joseph Locke (1805-1860).

Other railway engineers included Richard Trevithick (1771-1833) who designed steam carriages and high-pressure steam engines. His experience in mining led to an invitation to help in the construction of a tunnel beneath the Thames, a project later taken over by Marc Brunel. Sir Daniel Gooch (1816-1889) was the first locomotive superintendent of the Great Western Railway. He designed engines for Brunel’s board gauge system and was involved in laying the first successful trans-Atlantic telegraph cable using Brunel’s ss Great Eastern.

In 1843, Britain had nearly 2,000 miles of rail track. By 1870 this had increased to over 13,600 miles. The necessity of establishing a level surface capable of carrying track and train across diverse terrains led to what has been termed ‘the biggest earthmoving operation in the history of humanity’. Wealthy landowners were initially suspicious of the railway and feared it would unsettle their livestock and the local population, but they soon saw its potential and many made profitable investments in the new rail companies. By 1881, approximately 900,000 people were employed on the railways. British expertise was also used in constructing and equipping thousands of miles of overseas railway, a process described by author Anthony J Lambert as ‘one of the most enduring achievements of a period remarkable for its enterprise and industry’. In the city, there was a pressing need for additional transport to disperse the increasing quantities of people and goods that had arrived by rail. In 1863, in a bid to overcome the congestion of horse drawn traffic in London, an underground steam railway was built.

Travelling on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway

(Elton Collection: Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust)